(I had a dream where my Capoeira teacher Camarao asked me to write this essay, saying that it would be very important. I listened to it.)

The core idea is that movement classes in general, and Capoeira in specific, operate on a linear prescriptive model of learning that doesn’t align with how we now know complex movement skills emerge. It is the norm, for instance, for classes to be centered around a novel and complex movement sequence that is drilled out of context and never revisited again. Even players who can successfully perform the sequence often realize that something is missing, but do not have an alternative model of learning. The aim of this essay is to introduce an alternative paradigm for movement learning.

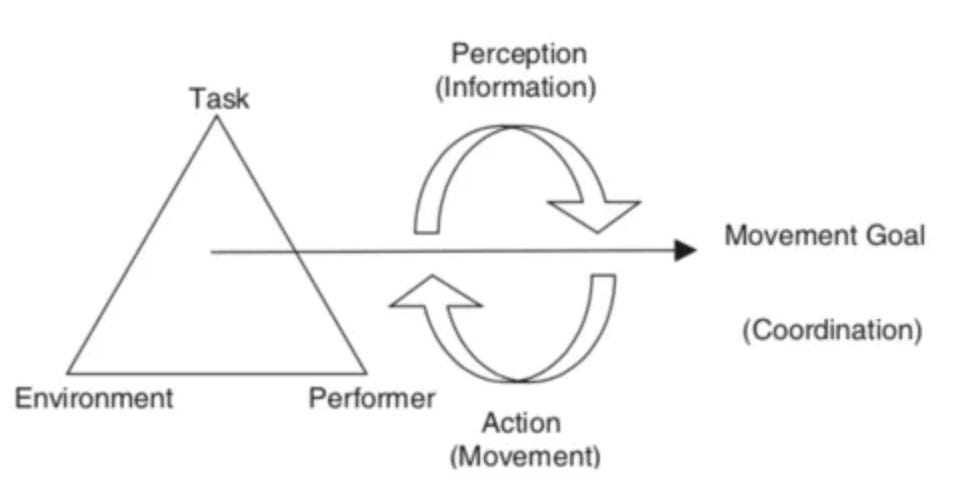

Core to this is the “constraints-led approach”. Under this approach, movement skills as emerging from the interaction between three key constraints: the task (what needs to be done), the environment (the physical and social context), and the performer (the individual's capabilities). As shown in the diagram, these constraints create a dynamic system where perception and action are cyclically linked - perception informs movement, and movement creates new opportunities for perception. This continuous feedback loop leads to coordinated movement solutions that achieve the goal. Rather than prescribing specific movements, this approach focuses on manipulating these constraints to guide learners toward discovering effective movement patterns.

We can take as a foundational metaphor the human as a complex dynamic system, as opposed to a mechanical static system. Among many things, this implies:

We cannot internalize moves by simple repetition (i.e., drilling), but rather by introducing several contexts in which the move can be initiated.

We cannot directly reshape our bodies, nervous systems, and thus our movement patterns. Instead, we add challenges that provide structure for our habits to form, which gradually our nervous systems and bodies will reshape around. This is similar to how, if we shade half of a young tree, it will naturally reshape and grow toward the sunlight. We do not need to control the direction that each root tip grows.

How "deeply" we internalize the move depends on the range of contexts you have mastered it in (e.g., Ginga from Kexada, Ginga from handstand).

Considering other findings from cognitive science, we can also add: If we recognize that the goal is competent expression in improvisation, using a wide breadth of movements in a roda, we should:

Favor mastery of a single movement and a wide variety of contexts

Perform movements in an environment realistically similar to the roda (e.g., heavily favor pair work)

In general, create conditions for creative solutions to movement challenges: we can create our own moves too!

Foster sensitivity: if we are carrying a refrigerator, we cannot tell if the weight of a fly is added. If we are carrying a feather, it is immediately obvious. By paying attention to subtle sensations and learning slowly, we can paradoxically internalize the movements more quickly.

Pay attention to inner comfort and pleasure over external appearance.

Practice observation: Watch two players playing together and teach students how to see better, because then they will be able to learn better.

We can also craft games around our weaknesses. For example:

Dodges: player one can only dodge; player two improvises and gradually adds challenge to player one by introducing new kicks until player one is just at their capacity

"Getting in sync": players rotate without warning with other players who come in and take their role

Getting started: practice improvising initiations at the beginning of the roda; create a novel approach

For more on the Constraints-Led Approach, see Rob Gray’s site.

This is very much how pedagogy in general should be, and there's no need to restrict it to movement.