On meaning #3: We who glimpse icebergs

invisible entities and how they can help us see more whole

We who glimpse icebergs

prior essay: in the world like lovers in love

I want to invite you into a short experiment. I promise it won’t take more than a minute.

First, see if you can notice your nose in your visual field. It might be hard to see with both eyes open, so you may want to close one eye before first taking a look.

Next, notice the moisture in your mouth, and pay attention to the next time you have the instinct to swallow. Humans swallow around once a minute, so it shouldn’t take too long.

Our nose is always in our visual field, but somehow we don’t ‘see’ it unless someone points it out. The same with our swallowing. They were in the background and invisible to you, yet also part of you, until I drew your attention to it.

Most of our being is invisible to us

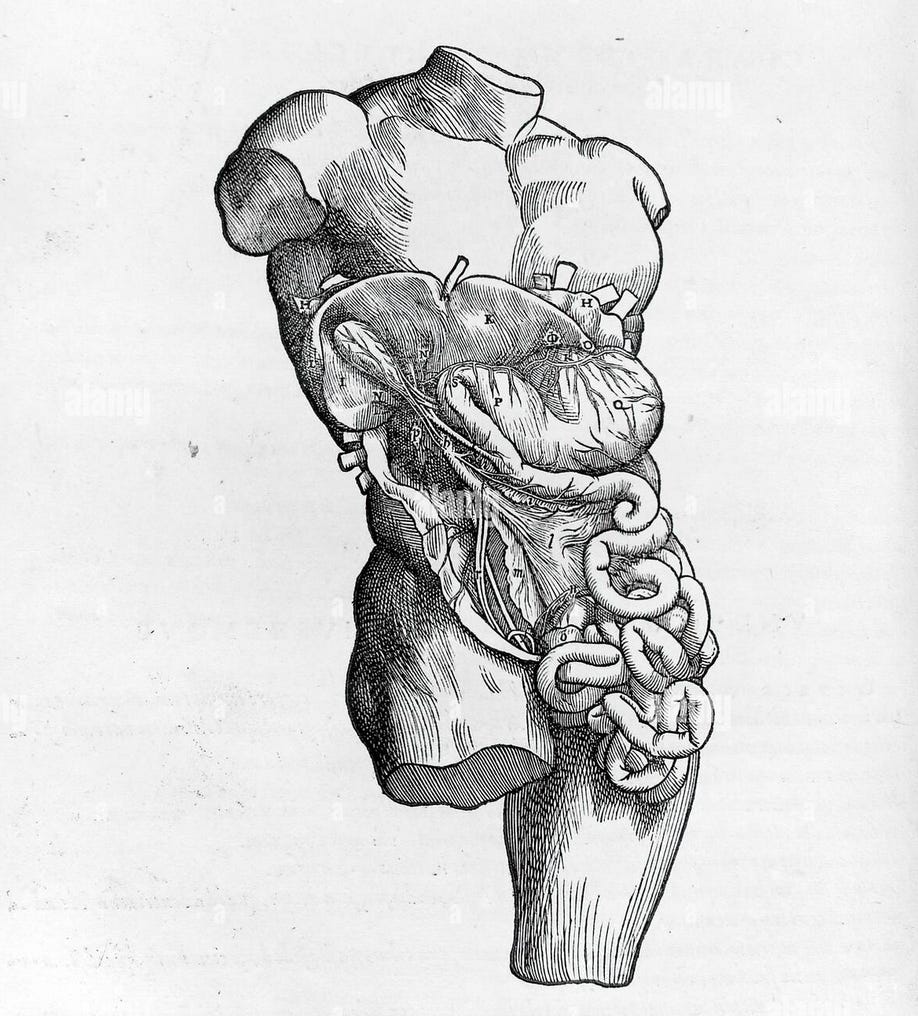

Our being involves much more than swallowing and seeing. I could also draw your attention to your stomach, your heartbeat, or other large organ systems. Depending on how you define an organ, we have about 80 organs in our body. They are a ruthlessly efficient orchestra that allows us to move, digest, breathe, mate, excrete, combat disease.

Our being is a deep well of motion, much deeper than we can begin to fathom. Nearly all of the processes that constitute us are invisible, happening in a background flow of activity. If our being is an iceberg, we only ever see the smallest flickering tip at a distance.

Now we can draw a distinction between these two modes: the backgrounded invisible mode, and the foregrounded visible mode of things1. By default, things are in an invisible background flow, but sometimes things become visible. But why does the invisible become visible?

Things become visible when there is a potential problem

It is mostly in response to potential breakdowns that the invisible becomes visible. You only notice your shoes when you need to put it on, or your shoelace is undone. Similarly, you see your phone screen when it cracks, or someone points it out to you. You might not even realize you had an appendix until a sudden pain in your lower abdomen strikes you as you wake up.

The crazy thing is that things have to become visible for us to think about them, and this has meant that most philosophers since Descartes have thought that only the ‘visible’ things exist.

Common science denies the invisibility of things

According to the common scientific view, as based on Descartes’ arguments, we are mind-stuff in a world of objects. Your hand, your phone, your shoes are just there and visibly apparent. According to the consumer theory of microeconomics, we make decisions by observing the objective choices between option A and B, and selecting the product that yields the higher utility2.

The options described here are already visible and perceived in the world. There is no room for the invisible background occurrence. The decision is apparently made by some disembodied mind-stuff, separate from the world.

This leads to unhelpful conclusions like “more choice is always better”. If we understand that choices — deliberation when stuff is visible to us — happen in response to potential problems, then we might see how more choice is not always better. Having the choice of ten different socks and twenty different shoes made visible to me each day would certainly make me miserable.

Accepting the invisibility of everything around, the limits of our perception, can bring us closer to a view of life not as a collection of problems, but as a beautiful motion, whole and in coherence with the environment us.

Joe Carlsmith writes:

“In so many ways, we are, indeed, as children. Barely not rocks. We barely have eyes, I suspect, relative to what it is possible; we never see near to whole; and what light can we see is almost too much, too bright. Still, we are here. We are free. We can try to look steady.”

Heidegger’s concept of the "ready-to-hand" refers to how objects are experienced when we are absorbed in using them without explicit reflective thought. In contrast, the "present-at-hand" is how objects are experienced when we disengage from our practical involvement and view them as objects for observation, analysis, or contemplation.

The shortcomings have long been recognized with behavioral economic models of human behavior. However, each economic behavioral model I’ve come across still makes the same mistake of denying the invisible ‘ready-to-hand’ continuity of humans.