On predictions

people as prediction engines, how i got better, a forecasting workshop

I was surprised to see an email last week from Scott Alexander telling me I had placed highly in the ACX 2023 prediction competition.

Back in January of 2023, I was still in Auckland, and remember being sprawled across my mother’s gray carpet, kissed by a patch of sunlight. I entered all my predictions in a furious four-hour flurry, ran outside and forgot about them entirely.

In honor of the occasion, I’m going to share a few disjoint thoughts I’ve gathered over the years on predictions.

Prediction is a deep feature of humans

Last year, I wrote that we are all individually and collectively amassing technical debt. One way of reframing my essay is that we are stuck in patterns that are no longer predictive.

Flinching each time a dog passes by may have made sense as a child in rural Tibet1, where stray dogs often attacked children, but in an urban center, the flinch becomes technical debt, a miscalibrated prediction. By integrating the relative safety of the new environment, the traumatic fear of dogs goes away. This is one way of seeing how all ‘trauma processing’ works — the prior ways of seeing the world, which may have made sense in the original environment, are updated in response to new information2.

We can reduce technical debt by paying attention to our predictions. Consciously noting our probabilistic prediction errors is one powerful way to do this.

How I got better at predicting

Two years ago, I became really curious about the top forecasters’ methods and started to message the Metaculus top scorers one by one. Luckily it wasn’t long before one of them agreed to have a call and do some joint forecasting. It turns out that there is no secret sauce. Just very close attention to detail. Even the best follow basic formula of i) find reference class/base rate, ii) update based off vibes/math.

Like Eli Lifland (a much better forecaster than myself), I think there are major diminishing returns on both i) practicing forecasting in general, and ii) thinking about a specific question after you’ve done the obvious approach. There’s a lot of irreducible uncertainty out there.

Having said that, I do think there’s a lot of room to improve on being able to make fermi estimates when base rates don’t exist, and to improve your vibe-sensitivity.

I really enjoy playing fermi estimate games with friends3. For years, I’ve also kept an excel spreadsheet that made informal predictions like “I will be glad I went to this party: 0.6” and then noted the result. This improved my vibe-sensitivity.

Writing your own forecasting questions may be more useful than forecasting

Forecasting on existing questions is useful to do because it is a cure for bullshit. However, writing your own questions forces you to face the bigger challenge of articulating what you care about.

At the beginning, I found myself without questions. Then I started to talk to curious friends and realized there were interesting questions in every conversation we had about the future.

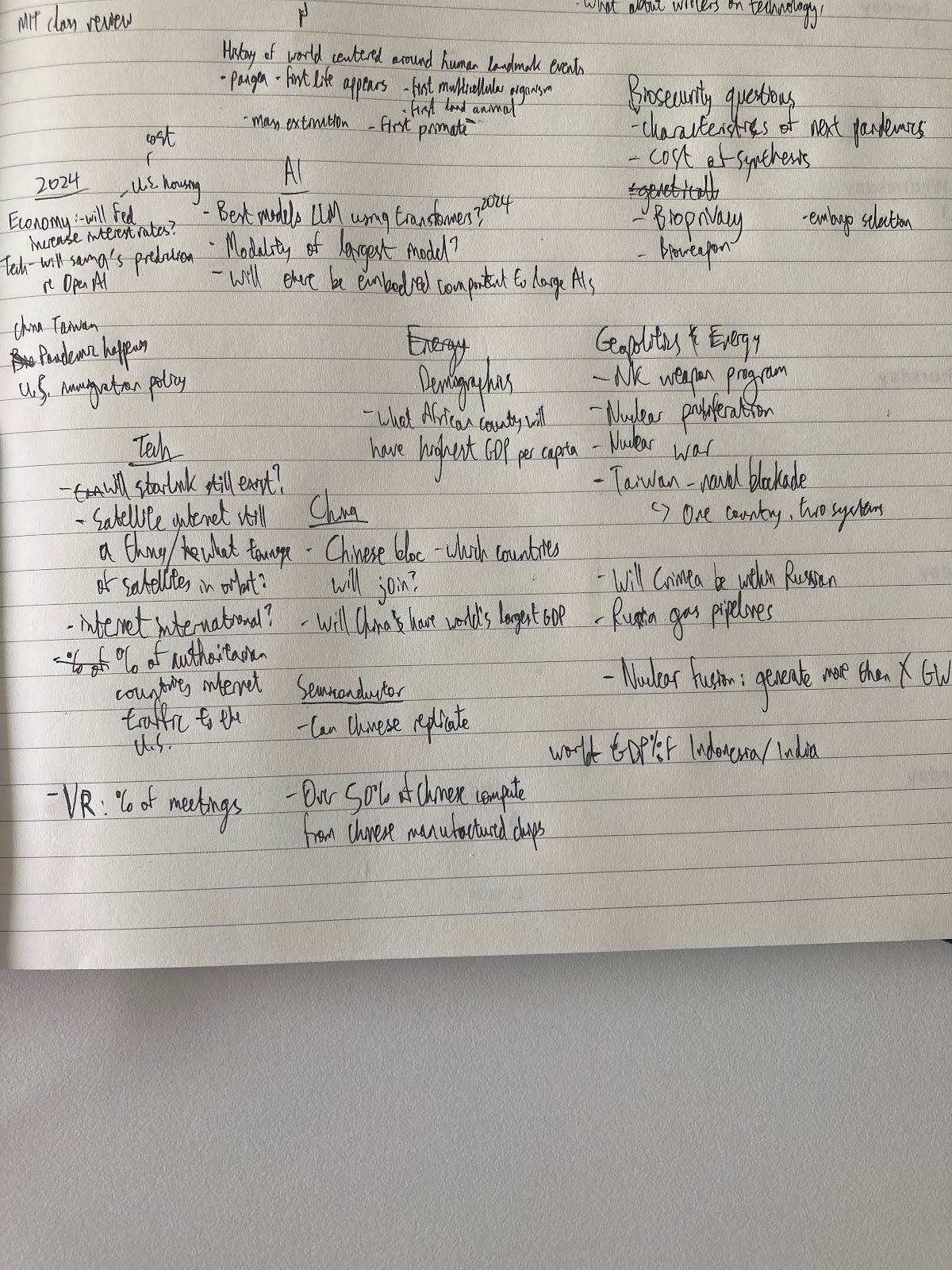

Writing questions is more like creative storytelling than math. The best questions are beautiful, provocative, and insightful all at once. “What fraction of the American voting population will identify as Mormon in 2050?”, “What countries will be clearly part of the China bloc in 2030?”, “What percentage of satellites in space will be American in 2040?”. These might be too vague to clearly adjudicate in a prediction market, but I find them beautiful because they orient me towards tides of influence that are otherwise invisible: demographics of religion, geopolitical alliances, the space race.

Unlike forecasting, there was no algorithm to follow for question generation. It’s a matter of realizing relevance, of cultivating taste.

Questions act on the world

I also noticed that questions have agency of their own. I used to think of forecasting questions as mostly inert, passively asking about a future that is ‘already there’. Now I see that each question comes out of a way of seeing, a particular vision of the future. Sometimes this is obvious (“Will you be ashamed that you wet your bed tomorrow morning?”) but sometimes it is quite subtle (“Will Trump win the 2024 Republican Presidential Nomination?” assumes that the nomination is not disrupted, for instance, by a pandemic).

The world is not a set of fixed objects moving according to laws we understand. Technology is not inevitable, and we might not have the right concepts to reason about the future yet. Change arrives like waves out of the ocean — with the right skill and luck, we can reorient ourselves and stay afloat.

P.S. given sufficient interest I am considering running a forecasting course. If you are interested, add your email here.

As an eight year old I spent a week aboard a donkey in the Himalayas around Tibet. Fortunately no stray dogs scared me.

There’s some empirical and theoretical basis for my analogy here. Coherence Therapy is basically calibration training but on the level of emotional schema (not cognitive concepts). See this recent paper introduces a predictive processing view of Coherence Therapy: Chamberlin, D. Eric. "The Active Inference Model of Coherence Therapy." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 16 (2023): 955558

For learning how to better estimate, Guesstimate is not bad, and lately I’ve been really enjoying Cell Biology By the Numbers